Posts

-

People who want to be machines

Two quotes from Wendell Berry:

-

Nine Mile Prairie

-

Not prestige, but community: my advice on grad school

There’s no shortage of such advice out there; consider this winsome and thoughtful post by Brad East, which puts the whole question in a properly theological key which I won’t try to better. However, the practical side of Brad’s post and some recent conversations with students have underlined for me that I offer different advice than most of my fellow professors do. I’m writing that advice out here in hopes that it will be of service to some, perhaps especially to those students who share with me a concern for values like place, community, and family—values to which graduate school has too often been hostile.

-

Odysseus and the attempt to impose order

Odysseus thinks of [his return home] as a cleansing, a return to goodness, but the poem knows that the desire for sweetness has ended only in horror and mayhem. He thinks that order can be imposed by will; the poem knows that the vision of perfection brings war into a house and leaves it broken and bloodied.

It is a sobering drama, an anti-Arcadia, with a deep lesson: singular visions do not work; only by consensus and accommodation can the good world be made; returning wanderers do not have all the answers; and anything which is to be done in your own Ithaca can only be done by understanding other people’s needs and their unfamiliar desires. Complexity, multiplicity, is all and clarified solutions come at a brutal price.

-

Magnanimous despair

The proper response to ideals we fail to attain—or indeed do not have the capacity to attain—is neither to lower the ideal nor to throw up our hands in bitter despair because we fail to reach the ideal. Rather, it is to allow our failure to become a kind of “severe mercy.” This phrase is from a letter that C.S. Lewis wrote to Sheldon Vanauken regarding the death of Vanauken’s beloved wife Davy. Perhaps, Lewis gently suggests, the loss of Davy might become “a mercy that was as severe as death, a death that was as merciful as love.” Losses and failures can become a mercy if they sharpen our longing for the glorious love we are created to participate in and embody. We weren’t created to be normies. We were created to be saints. And we ought to be dissatisfied with anything less. We will never be able to love our family members and neighbors as their eternal glory merits. But that failure attests to the incredible, not-yet-realized glory entrusted to us.

-

Reading diverse books is not about being nice

It has always bothered me that the very idea of paying attention to or knowing Indian history is tinged with the soft compassion of the do-gooder, as a kind of voluntary public service, like volunteering at an after-school program. But if we treat Indian stories this way, we do more than relegate Indians to history—as mattering only in relation to America’s deep and sometimes dark past. We also miss the full measure of the country itself. If you want to know America—if you want to see it for what it was and what it is—you need to look at Indian history and at the Indian present.

-

Ghosts of geography

What would you give

to have heaven be the way you imagine,

made of the familiar and welcoming? -

Dad theory

Good thinking enables us to transform something we don’t know into something we do. To use a spatial metaphor, the challenge is to bring something in the distance a little closer to us without collapsing the distance completely. Performing the miracle of cogitation is likely to leave us feeling a little smug about ourselves, the self-ruling princes of the intellectual realm. But dads know such autonomy is illusory.

My kids—if I can even use the possessive—are a part of me, but I cannot see them if I reduce them to my own reflection. Parenthood entails limitless closeness; all parents see more of their very young children than their kids can see of themselves. Being a dad, though, means perceiving this intimacy from a distance and working to make it outwardly manifest through awkward, conscious effort. This dialectical relationship resembles good thinking, which brings us to the first moment of Dad Theory. Dads guard against losing themselves in particularity, on one hand, and losing themselves in abstraction, on the other. Being a dad means being neither too attached to one’s own concerns to see things clearly, nor too impressed by speculation to see the messiness of real life. To practice Dad Theory is to negotiate with the known unknowns—and to trust that love is a stable point you can use to navigate through ambiguity to reach something solid and sure.

-

Those less dramatic human problems

There are kinds of human problems which really do seem, as our tidy expressions would have it, to “come to a head” and “demand to be dealt with.” But there are also problems, often just as serious, which come to nothing that we can recognize or openly deal with. Some long-lived, insidious problems simply slip us off to one side of ourselves. Some gently rob us of just enough energy or faith so that days which once took place on a horizontal plane become an endless series of uphill slogs. And some—like high water working year after year at the roots of a riverside tree—quietly undercut our trust or our hope, our sense of place, or of humor, our ability to empathize, or to feel enthused, and we don’t sense impending danger, we don’t feel the damage at all, till one day, to our amazement, we find ourselves crashing to the ground.

-

The risk of gentleness

A limb skimmed the inside of my belly, the slick slide of it like a marble rolling underneath my skin. A tiny baby boy jostled my insides, engaging in his regular evening ritual of chaotic movement. I sat feeling his unknown shape bump up against my own, considering all this child’s unknowns: the thickness of his hair, the hue of his eyes, the shape of his nose. Closer than a brother, yet more mysterious than a stranger.

-

Restoring the Midwestern landscape

Even while lamenting the ecological and economic costs of commodity-crop agriculture, many Midwesterners seem unable to conceive of our landscape without it. Wisconsin farmer Mark Shepard, however, refuses to take this claim at face value, arguing persuasively that “restoration agriculture”—a style of farming that models itself after the natural ecosystems of the Midwest rather than a manufacturing facility—can not only restore biodiversity but provide better nutrition and a better economic foundation for our communities.

-

Why we can't say the word 'abnormal'

There is the scientific and ideological language for what is happening to the weather, but there are hardly any intimate words. Is that surprising? People in mourning tend to use euphemism; likewise the guilty and ashamed. The most melancholy of all the euphemisms: “The new normal.” “It’s the new normal,” I think, as a beloved pear tree, half-drowned, loses its grip on the earth and falls over. The train line to Cornwall washes away—the new normal. We can’t even say the word “abnormal” to each other out loud: it reminds us of what came before. Better to forget what once was normal, the way season followed season, with a temperate charm only the poets appreciated.

-

On watery Nebraska

Notwithstanding the state’s name, which translates to “flat water” in archaic Otoe, or the facts that Nebraska has more miles of rivers and a larger quantity of groundwater than any other state, that the apocalypse should arrive in our arid Great Plains state via water, not fire, struck me as deeply implausible. Nonetheless, water has made Nebraska what it is. The frozen, prehistoric water of glaciers transformed the region’s geology in the Ice Age; the waters of the state’s rivers, the Missouri, the Platte, the Niobrara, shaped the state’s settlement patterns; the subterranean water of the giant, endangered Ogallala Aquifer drives the state’s land use policies and thus its politics; and now, river water has reshaped Nebraska once again.

Nebraska’s waters have had their shaping influence on me too. I grew up, if not quite on the banks of the Big Blue River, at least in close psychic proximity to it. In the summer its waters trickled through my thoughts.

-

Information super-abundance leads to nihilism

Information scarcity may lend itself to a measure of credulity: When facts are few, persuading the ignorant is relatively easy. But information abundance, already characteristic of early modern societies, engenders a degree of skepticism: The more there is to know, the more likely we feel that truth is elusive. Information super-abundance, or the condition of “digital plenitude,” as media scholar Jay David Bolter has called it, encourages the view that truth isn’t real: Whatever view you want to validate, you’ll find facts to support it. All information is also now potentially disinformation.

-

Tilling the rocky ridges

Permaculture gardening thus aims to create an enduring place, a habitation for human and non-human alike. This is not a quick process, and it may indeed involve hauling hundreds of pounds of limestone. Yet it promises a landscape not just prettied up and made a bit more fruitful, but restored to the sort of health it ought to have. I am unlikely to achieve that promise in my lifetime, in my place. (I am nowhere close to it now.) But the vision entices me still.

-

For gardeners, there is no time to waste

I really feel that if everyone would go back to nature and experience its joys, we wouldn’t have to wrory about people putting razor blades in candy. A lot of vandalism and crime is the result of boredom. I’m thinking . . . of people in this area who have nothing better to do than go to the corner tavern and drink beer and shoot pool. I’m also thinking of the white-collar crowd who loves to go have a “couple drinks” at a nice bar, waste a whole Saturday night at a cocktail party, or a whole Sunday watching ball games. You don’t find gardeners doing these things. Or even wanting to do them. For gardeners there is so little time in life, so much to do and enjoy. For gardeners, there is no time to waste!

-

Reading Julian of Norwich in a pandemic

Julian was a woman who had chosen, and made fruitful, just such enclosure as my correspondent was now enduring. Julian was a woman in a city many times menaced by plague, ill herself, who nevertheless through and in that illness sought a new intimacy with Christ and found his wounds touching and redeeming hers. She was an anchoress who had found again her anchor-hold in God, holding strong and steady amid the tides of panic and blame which turned and shifted around her.

Indeed, she swam against, and helped to turn, a tide of bad theology. In a time when illness was deemed to be a judgement from God and a sign of sin, Julian prayed to be made ill that she might come closer to Christ. In an age that considered outbreaks of infection to be a sign only of wrath and condemnation, she discerned that Christ knows and loves and holds us even and especially when we suffer, and that his meaning, his intent towards us in all things, is only love.

-

We need not reject the human to heal the land

Americans today little appreciate how European settlement transformed the landscape of this continent. Before colonization, old-growth forests dominated the East, chestnuts and hickories and old oaks in abundance. Across the Midwest, the prairies stretched for thousands of miles. Today, the forests remain in scattered fragments or stands of young second-growth timber, recovering from logging; the prairies are all but gone.

European settlers looked on the American landscape as virgin wilderness, and set out to subdue it. They first erred, though, not in the attempt to subdue, but in their very perception of the land. Their understanding of North America as a wilderness ignored the sophisticated land management practices of Native Americans. Though Europeans perceived them as primitive hunter-gatherers, in fact Native Americans transformed the American landscape. They cultivated edible species in the Eastern forests, promoting the chestnuts that once ruled the forest. They burned the prairies to keep land open for buffalo herds. They modified waterways and caused erosion damage. Far from a virgin landscape, North America appeared as it did when Europeans arrived because of human intervention.

-

Three decades of Midwestern goodbyes

Deanna Dikeman took a photo of her elderly parents waving goodbye each time she left their house in Sioux City, Iowa—at least once a year for 27 years. The collection carries the title “Leaving and Waving.” The photos document a particular moment experienced by all of us who live far from home: the final (for that visit, at least) exit from the driveway, the departure that carries one into separation and distance again, a moment that has brought me to wrenching, painful tears more than once. Given the chronology of the series, of course, we also witness much more about the changes brought about by time. I would urge you to check out the series:

-

Victor Lee Austin on the burial of a child

The disciples—we might think of them as trying to be Jesus’ “handlers”—they turned the children away. But Jesus felt strongly about this. He was indignant. He rebuked the disciples. Let the children come to me; do not hinder them. Jesus always wanted the children to come. There are stories of sick children that he visited. There was one, at least, that he raised back to life.

This is not—we must understand this—not sentimentality. He himself is going to die, die for those children, those adults, the men, the women, the slaves, the free people. He knows the hard things. And it is precisely not sentimentality in the midst of the hard things to see children, really to see them, to see that they are people, just like all people. Children aren’t future people, they aren’t people whose value or importance is in their future. They are people who, like all people, have their value and importance in the now. . . .

N.’s story is an unusual story: the hardness of cancer, the pain of treatments, the care that he required over many years. These are real things. But I have heard from you something that actually does not surprise me: a sense that a light was shining even in the midst of these difficult things. The light was sometimes in you, as you loved and cared for him, in others who were involved in his life, but also the light could sometimes be seen in N. himself. As you who have loved him share your memories, you will see, you will remember, that it was hard (we should never deny it was hard) but: it was not only hard.

So here is my unsentimental thing to say today. We all weep at death, and we should. We all wish N. had never had cancer, or that, having it, we wish it could have been cured. And so, of course, we wish his life had been longer, that he had died, say, at 70 rather than at 7. But when Jesus looks at N., he does not see tragedy. He does not see a short life that should have been longer. He sees N. himself, a person, a complete person just as he is.

-

Canoeing Nebraska and finding mystery

The clouds parted as we continued south, the sun licking pools from the asphalt. A meadowlark resting on a mile marker recited a Ted Kooser poem from memory—Scout’s honor. The Sandhills beg for poetry. “It is without a doubt the most mysterious landscape in the United States,” the late Jim Harrison once wrote in The New York Times. “… The vastness and waving of the hilly grasslands in the wind make you smell salt.” More cows than people. A loneliness endemic to this terrain, one of the largest grassland ecosystems in North America.

-

The four things my 6YO has to tell you about windows and blinds

Marking this completely unprompted bit of deductive reasoning from my 6YO down for posterity:

-

Learning to see the Plains again

The challenge of the immigrants who overran this country is now to grow up and settle down, reflect, and naturalize—to become part of the land we have built our homes upon. We can’t do that unless we learn to see the treasures who live here with us.

The American settlers who tamed the Plains looked with disdain upon the prairies they destroyed. They came from a land of trees, and saw nothing of value in the diverse community they plowed and grazed into oblivion. All they wanted was the thing that this community had spent thousands of years building: the rich soil beneath it. But the settlers were missing something. They had never tasted prairie turnip, prairie parsley, prairie clover tea, or poppy mallow root. Let us taste them now, close our eyes and dream, and admit our oversight. Listen hard enough, and you can still hear the hooves of bison, pawing in the dirt of soybean fields.

-

Tropical fruits in the Ozarks

The maypop shows, however, that localism need not mean confining oneself to an austere and moralistic diet. If I cannot grow bananas and mangoes in the Ozarks, I can nonetheless harvest maypops. I can plant fruits that boast a cornucopia of tropical flavors: native pawpaws and persimmons, or hardy exotics like jujubes and the vividly named “zombiefruit.” With a little creativity and attention to plants forgotten by our industrial systems, we can eat locally without sacrificing the pleasures of tropical flavors.

-

An ethos of abundance in ecological crisis

“Do more with less” is the ethos of austerity. “Do more with more” is the ethos of the abundant world to which we should aspire.

-

General Mills and regenerative ag

Regenerative agriculture can be practiced by organic and non-organic farmers alike, rendering the approach accessible to all types of farmers regardless of their starting point. General Mills frames its understanding of regenerative agriculture around five key principles championed by scientists and pioneering farmers like Gabe Brown: minimize soil disturbance, maximize diversity, keep the soil covered, keep a living root in the ground year-round and integrate livestock.

-

Bogost on Boynton

Rhythmic surprises—including beats that initially seem off—pervade Boynton’s work. I still trip over the first page of Hippos Go Berserk!: “One hippo, all alone.” Trying out different options on your kids is one of the books’ delights. Though joyous, early-childhood parenting is also weird and lonely, waves of affection breaking up against rocks of irritation. Teasing out the rhythm of a Boynton book offers a mental refuge from the tedium of reading to children who never tire of hearing the same story.

-

Faith in more than Not-Nothing

The faith I found proclaimed a sanctified world, and a redeemed one—an enchanted world, if you want to call it that—but one where meanings were concrete. It offered me not just a sense of emotional intensity, but a direction in which to channel it. It contained magic not for the sake of magic, but rather miracle for the sake of goodness. God died and came back from the dead not because magic was real, but because love was stronger than an unmagical world.

Where everything pointed to this one thing, which is that at some point God was made man, and died, and came back from the dead—which is an utterly absurd thing to say if you are not Christian, and even if you are. Fridays mean that Christ died and Christ is risen and that Christ will come again. So does rose quartz. So does a full moon.

It is a story not just about Not-Nothing, but about Something. It is a story not just about the possibility of a world with meaning in it, but a story about a world where the meaning is, quite specifically, and utterly fully, love.

-

Putting two things together

An apocalyptic sense of dissolution and an overwhelming fear that the center cannot hold tend to make us believe that we must find some grand, heroic solution to set things to rights. And we may feel that we need to ignore anything that would distract us from the single-minded pursuit of this solution. Yet [Wendell] Berry’s response to large-scale problems is the humble work of finding two things that belong together and putting them back together. Two things, not all things. He calls us to be a people who make things, who set to work fitting the broken pieces of our world back together.

-

Come, Holy Success

Entrepreneurialism has long served as a surrogate religion for millions of Americans. This shift is because often entrepreneurialism looks a lot better to our peers than a life of Christian discipleship. That’s not all our fault—the ad men have no small portion of the blame for this—but to the degree that we make Christianity look boring and unserious, we share some degree of responsibility.

-

Tomato hornworm is lurking at your door

I say gardening is mostly about heartbreak, then, partly as a form of self-protection, but also as a recognition that unbroken success is not the gardener’s lot. Living systems like a garden don’t permit of failure-proofing. No matter how long you have gardened or how scientific your methods, drought, blight, and tomato hornworm yet lurk at your door.

-

The hermeneutics of mystery

The refusal of interpretation is itself a mode of interpretation

-

Hopkins the comet

—I am like a slip of comet,

Scarce worth discovery, in some corner seen

Bridging the slender difference of two stars,

Come out of space, or suddenly engender’d

By heady elements, for no man knows:

But when she sights the sun she grows and sizes

And spins her skirts out, while her central star

Shakes its cocooning mists; and so she comes

To fields of light; millions of travelling rays

Pierce her; she hangs upon the flame-cased sun,

And sucks the light as full as Gideon’s fleece:

But then her tether calls her; she falls off,

And as she dwindles shreds her smock of gold

Amidst the sistering planets, till she comes

To single Saturn, last and solitary;

And then goes out into the cavernous dark.

So I go out: my little sweet is done:

I have drawn heat from this contagious sun:

To not ungentle death now forth I run. -

Something underneath

-

Gardening and madness

“I guess it’s true what they say, that it’s a fine line between gardening and madness.”

-

The doxological defense of Marilynne Robinson

Robinson’s most famous character, the Congregationalist minister John Ames, is devoted to Calvin—as is Robinson herself. She is a careful student of the Reformer and mimics his form: The Gilead novels, like the Institutes, should be read as a summa pietatis rather than a summa theologiae. This means that for both Calvin and Robinson, the goal is doxology.

The Institutes’ subtitle describes the work as “almost the whole sum of piety and whatever is necessary to know about the doctrine of salvation.” In the same vein, Robinson seeks to express in her novels a theology that has worship as its end. In her work, delight in the created order is a precursor to knowledge of God’s sustaining presence.

-

High church megachurch?

New Life Downtown now concludes its Sunday service with a beautiful a capella rendition of an Anglican Doxology, a hymn of praise to the Trinity. Doxologies are found in eucharistic prayers and Catholic devotions like novenas and the rosary, time out of mind, but when was the last time you heard a doxology sung in a Roman Catholic church? In practice, many Roman Catholic churches have become increasingly low church. . . . So what is happening at New Life is noteworthy. More intriguing yet, it is happening at evangelical megachurches and formerly iconoclastic mainline churches all across the country. Whether it is a move of the Holy Spirit toward greater unity or cultural appropriation on a massive scale, old school Catholic practices are in. Yes, that celebrity Protestant pastor is wearing a stole with Our Lady of Guadalupe on it.

-

Building topsoil fast with biodiversity

Historically, some experts have said it takes three hundred to a thousand years to build inches of topsoil. But we’ve learned that’s actually not the case. Soil is not built primarily by decaying leaf matter and so forth. Living, healthy topsoil is created by plant root exudates – the carbohydrates, vitamins, organic acids, and other nutrients released into the soil by the root systems of plants. Of the sugars that plants create through photosynthesis, 30–40 percent transfers to the soil through the roots in exchange for nutrients. In this way, plants feed soil biology: fungi, bacteria, microorganisms, and mycorrhizae, the symbiotic associations between plants and fungi in the root zone. Those take the sugar and convert it to humus, which is topsoil.

So topsoil can actually be built quite quickly. But it won’t happen without diverse plant life. This diversity is key, and it has everything to do with the way we farm.

It’s a cutting-edge area of scientific research. We’re learning that as plant diversity increases, there’s a certain trigger point – called quorum sensing – where topsoil begins to build rapidly. How many species of plants do you need for a quorum? The more the merrier, microbiologists are saying. Different plants produce different root exudates, allowing access to specific soil nutrients. There have been positive results from as few as twelve species, and more rapid success with forty.

Our best native pastures at Danthonia contain fifteen to twenty species. We’re a long way from the hundreds of species these landscapes once enjoyed – all forming a richly diverse pasture sward that allowed topsoil to build and be maintained, enabling it to hold water and release it during drought.

-

Nostalgia for the unknown

As austerely down-to-earth as the modal melodies of Appalachian folk music can sound, they can also convey profound pining. “The tenderness of a folk song does not arise only from nostalgia about how wonderful everything is back home,” the feminist theologian Wendy Farley once wrote. “Whatever the particularities from which this nostalgic longing arises, it continues to wound our hearts because it is also nostalgia for something no one has ever experienced.” In handed-down tunes, she recognized “desire’s refusal to accept the limitations of life.”

-

RIP to the singular Gene Wolfe

Gene Wolfe is a writer like nobody else, and although I can’t say that I’m an expert on his oeuvre, I have read more than a little of it. (The Wizard Knight is my favorite and a good place to start.) I have been reading some tributes and criticism in light of his recent death, of which the best pieces so far are Brian Phillips’s unsummarizable biographical treatment and this wonderful long essay by Kim Stanley Robinson which reveals a key piece of information about one of Wolfe’s best-known novels. Spoilers, obviously, await.

-

IVF and evangelical moral flippancy

We tear apart what God has joined together only at grave peril to ourselves: By dividing sex from procreation, we reconfigure the form which God has laid down for us to understand the nature of his agency in bringing new life into the world. If a people who emphasize the gospel cannot say no to that division, we are a people unworthy of our name.

-

Welcoming the other

Trust is impossible in communities that always regard the other as a challenge and threat to their existence. One of the profoundest commitments of a community, therefore, is providing a context that encourages us to trust and depend on one another. Particularly significant is a community’s determination to be open to new life that is destined to challenge as well as carry on the story.

-

Madeleine L'Engle and the Modern Moral Order

Along with all the greatest writers of the fantastic, the Inklings offer an alternative to (if not a dissent from) what Charles Taylor calls the Modern Moral Order: a rational ethic of individual rights governed by moral laws aimed at maximizing temporal happiness. The Modern Moral Order encourages us to evaluate our moral decisions in light of rational calculations about tangible goods and bads—does one’s chosen sexual indulgence, for instance, hurt anyone?—rather than assessing them via transcendent sources, the Tao or the Ten Commandments. The removal of these common sources further drives moral decision-making back to individuals, eroding our common moral language until it’s little more than a veneer over the id, with moral arguments made on the basis of appeals to personal authenticity, “self-care,” or chosen identities.

For all L’Engle’s explicit spirituality, her works show a greater comfort with the Modern Moral Order than one might expect from a writer so often associated with the antimodern Inklings.

-

Trees are not trees until so named

Yet trees are not ‘trees’, until so named and seen

and never were so named, till those had been

who speech’s involuted breath unfurled,

faint echo and dim picture of the world,

but neither record nor a photograph,

being divination, judgement, and a laugh

response of those that felt astir within

by deep monition movements that were kin

to life and death of trees, of beasts, of stars:

free captives undermining shadowy bars,

digging the foreknown from experience

and panning the vein of spirit out of sense.

Great powers they slowly brought out of themselves

and looking backward they beheld the elves

that wrought on cunning forges in the mind,

and light and dark on secret looms entwined.

He sees no stars who does not see them first

of living silver made that sudden burst

to flame like flowers beneath an ancient song,

whose very echo after-music long

has since pursued. There is no firmament,

only a void, unless a jewelled tent

myth-woven and elf-patterned; and no earth,

unless the mother’s womb whence all have birth.

The heart of Man is not compound of lies,

but draws some wisdom from the only Wise,

and still recalls him. -

Seed catalogs are inveterate tempters

Gardeners are a modest and sober breed, not much given to the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, or the pride of life. We are generally free of covetousness (save towards our neighbor’s early tomato), rage (unless a rabbit gets into our lettuce patch), or sloth (unless it’s raining outside and the bean patch needs to be weeded). We all have our weaknesses, however, and for most gardeners the moral Waterloo must be fought during seed catalog season.

Seed catalogs arrive in the darkest part of winter, when the heart cries out for a sight of fresh vegetation. Into this parched landscape of the soul they introduce scintillating photography and descriptions of fruits and vegetables that may as well have been plucked from the vineyards of Canaan. Every heirloom tomato has better flavor than the last; each winter squash has the potential to grow to record size. Seed catalogs, in short, are inveterate tempters. No gardener, however ascetic, manages to resist their blandishments forever.

-

The floods lay bare the real Nebraska

Floods lay bare that which was already true. This is what the Genesis Flood does, of course, and it is also how Peter describes the coming judgment at the end of all things. He likens it Noah’s flood, going on to say, “the earth and everything done in it will be laid bare” (2 Peter 3:10).

Athanasius argues that miracles are often a kind of supernaturally accomplished acceleration of natural events: Nature will, given enough time, turn water into wine—rains will fall and nourish grape vines, the grapes will be harvested, and then eventually ferment to become wine. Jesus simply sped the process up at the wedding in Cana. Events like a flood, then, might be read as an inversion of a miracle—a rapid acceleration of the unmaking of the cosmos following the events of Genesis 3.

Sadly, I cannot help but see this quickening destruction happening in my home state. The flood has soaked thousands of homes and hundreds of businesses to ruin in places that already struggled with a trajectory of economic decline and despair brought about by forces outside their control.

-

Woods are spooky

Woods are not like other spaces. To begin with, they are cubic. Their trees surround you, loom over you, press in from all sides. Woods choke off views and leave you muddled and without bearings. They make you feel small and confused and vulnerable, like a small child lost in a crowd of strange legs. Stand in a desert or prairie and you know you are in a big space. Stand in a woods and you only sense it. They are a vast, featureless nowhere. And they are alive.

So woods are spooky. Quite apart from the thought that they may harbor wild beasts and armed, genetically challenged fellows named Zeke and Festus, there is something innately sinister about them, some ineffable thing that makes you sense an atmosphere of pregnant doom with every step and leaves you profoundly aware that you are out of your element and ought to keep your ears pricked. Though you tell yourself it’s preposterous, you can’t quite shake the feeling that you are being watched. You order yourself to be serene (it’s just a woods for goodness sake), but really you are jumpier than Don Knotts with pistol drawn. Every sudden noise—the crack of a falling limb, the crash of a bolting deer—makes you spin in alarm and stifle a plea for mercy. Whatever mechanism within you is responsible for adrenaline, it has never been so sleek and polished, so keenly poised to pump out a warming squirt of adrenal fluid.

-

Green, the Color of Truth

Because of etymology: vert, verus. Thus, in English, verity, verisimilitude, and veridical, but also verdigris, verdure, and verdant. Thus, literary representations of truth as green, as in the allegorical four daughters of God―Justice, Truth, Mercy, and Peace―who first appear in Psalm 85. By the time they feature in the medieval play The Castle of Perseverance, they are chromatically clothed, with Truth sporting chartreuse.

-

Art's concordence with doctrine

I do not think that art has to illustrate a slice of Christian doctrine to be true, but if Christian doctrine is true, then a piece of art’s concordance with that doctrinal shape might be one index of the art’s truthfulness.

-

The writer safekeeping enchantment

As a writing man, or secretary, I have always felt charged with the safekeeping of all unexpected items of worldly or unworldly enchantment, as though I might be held personally responsible if even a small one were to be lost.

-

Beauty awakens us to the real

To what serves mortal beauty ‘ —dangerous; does set danc-

ing blood—the O-seal-that-so ‘ feature, flung prouder form

Than Purcell tune lets tread to? ‘ See: it does this: keeps warm

Men’s wits to the things that are; ‘ what good means—where a glance Master more may than gaze, ‘ gaze out of countenance.

Those lovely lads once, wet-fresh ‘ windfalls of war’s storm, How then should Gregory, a father, ‘ have gleanèd else from swarm- èd Rome? But God to a nation ‘ dealt that day’s dear chance.

To man, that needs would worship ‘ block or barren stone,

Our law says: Love what are ‘ love’s worthiest, were all known;

World’s loveliest—men’s selves. Self ‘ flashes off frame and face.

What do then? how meet beauty? ‘ Merely meet it; own,

Home at heart, heaven’s sweet gift; ‘ then leave, let that alone. Yea, wish that though, wish all, ‘ God’s better beauty, grace. -

Relatable art is incurious art

To be relatable, art must also be incurious, not really interested in the mechanisms of why people are what they are, the texture of their lives, or the objects around them. To be interested in these things is to generate friction between the reader and the text, or at least to elude easy points of identification.

-

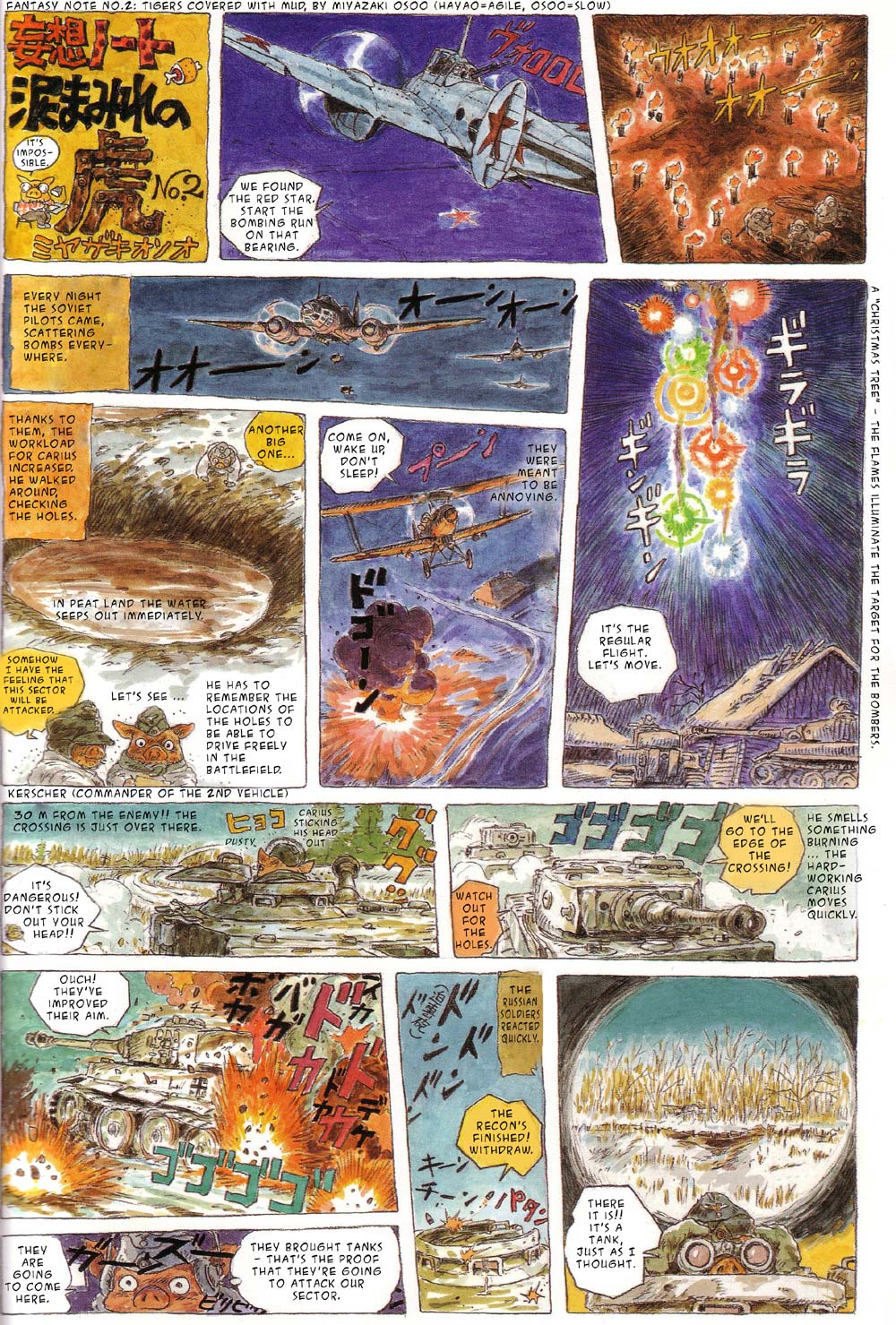

Miyazaki's Tigers in the Mud

-

The House

Sometimes, on waking, she would close her eyes

For a last look at that white house she knew

In sleep alone, and held no title to,

And had not entered yet, for all her sighs. -

Life resists minimalism

Actually, a love of nature is very important to the critique of minimalism. When I showed the image of the balcony with flowerpots, one of the reasons it seemed to have life was because it did have actual life. Our spaces can appear most dead and miserable when they don’t have any plant or animal life, when we have literally killed every single living thing that once inhabited a patch of ground. I was at the airport the other day, and I suddenly felt incredibly pained and uncomfortable, like I couldn’t breathe. I had a strong sensation that I was in a dead place, a kind of hell where nothing lived. I could not see a single plant. Everything around me was gray, dismal. It was tarmac and hallways. It depressed the hell out of me, because I think gardens should be everywhere. (Imagine, if you will, airport hallways that were made of trellises covered in vines and flowers, a terminal that felt like a greenhouse. Perhaps some birds in the rafters, crapping on the occasional traveler to remind them that there are worse problems than a delayed flight. But no snakes, for obvious reasons.)

-

Speech fulfills creation

But man’s ordering-to-flourish as its ruler is a necessary condition for the rest of creation to fulfill its own ordering. His rule is the rule which liberates other beings to be, to be in themselves, to be for others, and to be for God. And this he does by the rational speech with which he articulates the praise of God to which the whole creation is summoned. The bulwark against chaos is established “out of the mouths of babes and sucklings”.

-

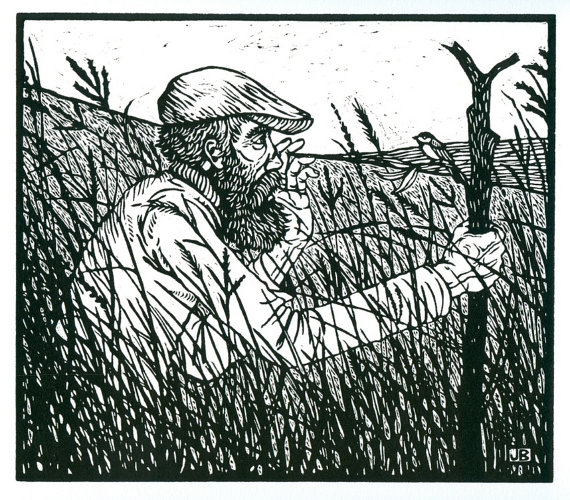

To have the land around you like clothing

Hunting in my experience—and by hunting I simply mean being out on the land—is a state of mind. All of one’s faculties are brought to bear in an effort to become fully incorporated into the landscape. It is more than listening for animals or watching for hoofprints or a shift in the weather. It is more than an analysis of what one senses. To hunt means to have the land around you like clothing.

-

Neither drought, nor busyness, nor squash vine borers

The trouble with gardening, however, is that once you’re in love—and I mean really in love—it’s for keeps. No amount of discouragement or unpropitious circumstance is going to uproot that mysterious tangle of delight and desire from your heart. Like all the great loves in history, love of gardening persists, often in the face of impossible odds. At unlooked-for times, and in unlooked-for ways, the passion ignites, and you remember what you knew as a girl: even if the end result doesn’t live up to the promise—even if the promise is unattainable this side of heaven—the desire itself is sweet enough to make up for it.

What’s more, the thing the promise points to is real, and your effort to incarnate it in an orderly vegetable patch or a flowerbed of flaming color is to claim a bit of Eden on a weed-choked, hard-crusted old earth still dreaming of a beautiful past and a redeemed future.

You rejoice to find that neither drought, nor busyness, nor squash vine borers have power to snuff out that original spark, and that a seed catalogue, or a fleck of green on an otherwise dead-looking hydrangea cutting can still summon a quick rush of tears. Of all things.

-

Dealing well with our helplessness

Too often our ethics assumes unmitigated agency. Robert Adams reminds us of the reality of helplessness. Ethics needs to include “dealing well with our helplessness.” pic.twitter.com/Qpv6ULSKUT

— James K.A. Smith (@james_ka_smith) November 10, 2018 -

We only enter truth through charity

I do not speak here of divine truths, which I shall take care not to comprise under the art of persuasion, because they are infinitely superior to nature: God alone can place them in the soul and in such a way as it pleases him. I know that he has desired that they should enter from the heart into the mind, and not from the mind into the heart, to humiliate that proud power of reasoning that pretends to the right to be the judge of the things that the will chooses; and to cure this infirm will which is wholly corrupted by its filthy attachments. And thence it comes that whilst in speaking of human things, we say that it is necessary to know them before we can love them, which has passed into a proverb, 1 the saints on the contrary say in speaking of divine things that it is necessary to love them in order to know them, and that we only enter truth through charity, from which they have made one of their most useful maxims.

-

Liturgy as self-defense

The higher Christian churches—where, if anywhere, I belong—come at God with an unwarranted air of professionalism, with authority and pomp, as though they knew what they were doing, as though people in themselves were an appropriate set of creatures to have dealings with God. I often think of the set pieces of liturgy as certain words which people have successfully addressed to God without their getting killed. In the high churches they saunter through the liturgy like Mohawks along a strand of scaffolding who have long since forgotten their danger. If God were to blast such a service to bits, the congregation would be, I believe, genuinely shocked. But in the low churches you expect it any minute. This is the beginning of wisdom.

-

There is no one but us

A blur of romance clings to our notions of “publicans,” “sinners,” “the poor,” “the people in the marketplace,” “our neighbors,” as though of course God should reveal himself, if at all, to these simple people, these Sunday school watercolor figures, who are so purely themselves in their tattered robes, who are single in themselves, while we now are various, complex, and full at heart. We are busy. So, I see now, were they. Who shall ascend into the hill of the Lord? or who shall stand in his holy place? There is no one but us. There is no one to send, nor a clean hand, nor a pure heart on the face of the earth, nor in the earth, but only us, a generation comforting ourselves with the notion that we have come at an awkward time, that our innocent fathers are all dead—as if innocence had ever been—and our children busy and troubled, and we ourselves unfit, not yet ready, having each of us chosen wrongly, made a false start, failed, yielded to impulse and the tangled comfort of our pleasures, and grown exhausted, unable to seek the thread, weak, and involved. But there is no one but us.

-

Time is eternity's pale interlinear

Here is the fringey edge where elements meet and realms mingle, where time and eternity spatter each other with foam. The salt sea and the islands, molding and molding, row upon rolling row, don’t quit, nor do winds end nor skies cease from spreading in curves. The actual percentage of land mass to sea in the Sound equals that of the rest of the planet: we have less time than we knew. Time is eternity’s pale interlinear, as the islands are the sea’s. We have less time than we knew and that time bouyant, and cloven, lucent, and missile, and wild.

-

Self-examination and self-forgetfulness

You can learn a lot by looking inside yourself. Still, in the end, I would rather look out.

-

Ivar's barefoot spirituality

“Ivar,” Signa asked suddenly, “will you tell me why you go barefoot? All the time I lived here in the house I wanted to ask you. Is it for a penance, or what?”

“No, sister. It is for the indulgence of the body. From my youth up I have had a strong, rebellious body, and have been subject to every kind of temptation. Even in age my temptations are prolonged. It was necessary to make some allowances; and the feet, as I understand it, are free members. There is no divine prohibition for them in the Ten Commandments. The hands, the tongue, the eyes, the heart, all the bodily desires we are commanded to subdue; but the feet are free members. I indulge them without harm to any one, even to trampling in filth when my desires are low. They are quickly cleaned again.”

-

Planting trees is inexpensive pleasure

For one thing, planting a tree offers inexpensive pleasure. Bareroot plants may cost as little as $25, require no fertilizer in the first year, and only need (where I live) a little protection from deer in the form of a tree tube or bit of fencing. Mulch is helpful, but this can often be gotten for free. With no more expense, I buy myself hours of enjoyment, from poring over nursery catalogs (an exercise in unmitigated concupiscence), to the excitement of planting day, to the light and satisfying work of pruning and maintaining a young tree. Even if I never taste a single apple, the process of planting and tending a tree offers me a satisfaction that I find it difficult to deny myself.

-

All great civilizations are based on parochialism

Parochialism and provincialism are opposites. The provincial has no mind of his own; he does not trust what his eyes see until he has heard what the metropolis - towards which his eyes are turned - has to say on any subject. This runs through all activities. The parochial mentality on the other hand is never in any doubt about the social and artistic validity of his parish. All great civilizations are based on parochialism - Greek, Israelite, English.

-

Scrooge and unmerited grace

While Scrooge’s redemption involves some good deeds—the Muppets and Dickens both have him, moments after awakening from his last ghostly journey, buy a Christmas turkey for Bob Cratchit’s family and make a donation to the philanthropists he earlier spurned—it would be a mistake to attribute his redemption to his own work. When he promises to “honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year,” he is accepting the gift that he has been given, an act as important in his moral transformation as his own turn toward generosity. He places himself in debt—to his damned friend who has intervened for him; to the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come; and to his nephew, whose consistently refused hospitality Scrooge at last accepts.

Having dedicated his life to demanding the repayment of debts, Scrooge incurs a debt he cannot repay. It is not enough to reject his old rules; he must become guilty before them as he reckons with his guilt under the standard he now accepts. That guilt, like this debt, will always remain. His redemption is also a fall. But under the new rules, debt becomes gift. Everything has changed.

-

The Midwest teaches us to look and see

The lesson these places teach is that beauty is not always, or at least not only, big, grand, sweeping, and sensational. It is also, and quite often, to be found in the small, the ordinary, and the plain. If these things are known well and patiently, their grandeur can reveal itself to us. Those who have known the golden light of evening to stream through stalks of corn, or who have seen the way that light transfigures a common ash tree, will know what I mean, and anyone who has beheld a Midwestern hillside painted with a wash of watercolor earth tones on a rainy September day will know it, too. The truth is that, in the words of the poet Hopkins, all of nature’s darling’s share a freshness deep down. They have the potential to shock us with wonder if they catch us when we’re ready to receive them.

Maybe it makes some kind of sense, then, that many of our greatest nature writers, like John Muir and Aldo Leopold, have come from places like Iowa and Wisconsin. I wonder if it might have to do with the way this landscape teaches you how to look and see, how to sit attentively long enough to let the poetry of things reveal itself to you. It helps not to be hemmed in by the sort of sprawling conurbations now enveloping our coastal cities. It helps to be so intimately connected with rural life. It helps to have the room to breathe free, to stretch out, to move in the liberty that only the wide-open calm of this stretch of country provides.

-

The problem with artifacts

NPR recently ran a fascinating piece on the redefinition of the kilogram. Turns out, the kilogram is actually a hunk of metal in France. When somebody needs to know exactly how much is a kilogram, they have to go take the hunk of metal out from beneath its special glass container with its special lifting tool (no touching the kilogram!) and weigh it.

-

The Princess Bride is about friendship

Friendship—loyal, ribbing, hard-won, true—can actually happen. Kids of all ages know this. It may play out differently in real life—perhaps “breaking down a door for your friend so they can kill someone” takes the form of helping a friend move apartments or reporting on the whereabouts of his or her ex upon request—but friendships of this nature have more wherewithal than Westley and Buttercup’s relationship. The Inigo/Fezzik (“and kind of Westley”) dynamic is responsible for the magic in The Princess Bride that crosses generations. Here are outsiders who band together. Here are reminders that life is less about perfect romances between perfect people than it is about imperfect friendships with imperfect people.

-

The timelessness of waiting on an airplane

If one can get past the frustration, there’s something magical about airport time. I’m not talking about the rush of getting through security and to your gate before boarding begins, or making a connecting flight or sitting on the airplane itself. I’m talking about the two hour layover or the delayed flight. It is one of the few times left in our society when waiting is the most productive thing to do, where there is no one person to blame (however ill-informed that decision when we are required to wait is anyway). The clerk at the DMV may be slow, but an airplane just is or isn’t there and you just are or aren’t on one. Airport time provides a singularly enforced experience of productivity-stifling and potential-producing patience. You can nap, or read a book, or get lunch, or stare out of the window. You can catch up on emails or make a call or play a mindless game on your phone. But none of these actions escape the atmosphere of the wait or change the dimensions of how long that wait will last. Elsewhere in the world, writing an email takes up the time it takes up, and playing a game wastes the time it wastes. But when waiting in an airport, because you cannot move the clock on the screen, because you are at the mercy of a network of forces mechanical and professional, how you use that time is the least teleologically ordered to your life’s schedule than it will ever be. Because the time is less yours than usual, it makes you more free in that time than you usually are. It is quite a peculiarity: airport time confers an atmosphere of timelessness precisely because of how rigidly timeful it is.

-

That time I almost tipped over a two-ton moving truck

I felt the bulk of all my worldly goods quite forcefully a few months ago when I almost tipped over the two-ton moving truck that contained them. After sweating my way through the narrow streets of St. Louis and keeping my foot to the floor in order to keep up with flow of traffic on the highway, the most frightening moment of my time as amateur trucker came in the final two hundred feet, right outside our new house. We live in a rural area of the Ozarks in southern Missouri, and our home rests on the side of what we generously term a mountain. Our narrow, sloping gravel driveway terminates by curving between a ravine and a drainage ditch at a point that, as it turns out, is not wide enough for the largest truck you can get from Budget. Accordingly, as I pulled up to the house, I rolled one set of the rear tires through the ditch, tearing a large chunk out of the lawn and causing the fully loaded truck, and my heart, to buck and twist like a breaching orca.

-

The mystic character of the cottonwood

A people living with nature, and largely dependent upon nature, will note with care every natural aspect in their environment. Accustomed to observe through the days and the seasons, in times of stress and of repose, every natural feature, they will watch for every sign of impending mood of nature, every intimation of her favor and every monition of her austerity. Living thus in daily association with the natural features of a region some of the more notable will assume a sort of personality in the popular mind, and so come to have a place in philosophic thought and religious ritual.

The cottonwood [the Plains Indians] found in such diverse situations, appearing always so self-reliant, showing such prodigious fecundity, its lustrous leaves in springtime by their sheen and by their restlessness reflecting the splendor of the sun like the dancing ripples of a lake, that to this tree they ascribed mystery. This peculiarity of the foliage of the cottonwood is quite remarkable, so that it is said the air is never so still that there is not motion of cottonwood leaves. Even in still summer afternoons and at night when all else was still, they could ever hear the rustling of cottonwood leaves by the passage of little vagrant currents of air. And the winds themselves were the paths of the Higher Powers, so they were constantly reminded of the mystic character of this tree.

-

Traveling in deep landscapes

Rand McNally travelers who see a region as having borders will likely move in only one locality at a time, but travelers who perceive a place as part of a deep landscape in slow rotation at the center of a sphere and radiating infinite lines in an indefinite number of directions will move in several regions at once.

-

Great missed opportunities in branding

Springfield, Missouri’s St. George’s Donuts –> St. George and the Donut

-

A big, loose, empty feeling

In fact, I had not cried when my grandparents drowned. In fact, I had not even felt sad when my grandparents drowned, at least not in the way I understood the word. What I felt was something else, a big, loose, empty feeling, and the right words for it didn’t seem to come from the language of emotions at all. I didn’t think I was wrong to feel this way, exactly. But I sensed that in some way it was a wrong answer, an answer that lay outside the interpretive paradigm we were meant to be working within, so without really thinking about it I told the therapist a story I thought he would know how to explain.

Note that I never imagined I might not understand what he was looking for. Only that it would be impossible for him—for other people, possibly for anyone—to understand me.

Where on earth, at eleven years old, had I gotten the idea that it was my job to be easily understood?

-

Limits and markers make travel possible

There are several ways not to walk in the prairie, and one of them is with your eye on a far goal, because you then begin to believe you’re not closing the distance any more than you would with a mirage. My woodland sense of scale and time didn’t fit this country, and I started wondering whether I could reach the summit before dark. On the prairie, distance and the miles of air turn movement to stasis and openness to a wall, a thing as difficult to penetrate as dense forest. I was hiking in a chamber of absences where the near was the same as the far, and it seemed every time I raised a step the earth rotated under me so that my foot fell just where it had lifted from. Limits and markers make travel possible for people: circumscribe our lines of sight and we can really get somewhere.

-

Argumentum ex silentio

The fact that God hides himself in the midst of revealing himself is paradoxically a testimony to his reality. Presence-in-absence is the theme of his self-disclosure. God isn’t hidden because we are too stupid to find him, or too lazy, or not “spiritual” enough. He hides himself for his own reasons, and he reveals himself for his own reasons. If that were not so, God would not be God; God would be nothing more than a projection of our own religious ideas and wishes.

The Lord hides himself from us because he is God, and God reveals himself to us because God is love (1 John 4:8). Does that make sense? Probably not—but sometimes Christians must be content with theological paradox. To know God in his Son Jesus Christ is to know that he is unconditionally love unto the last drop of God’s own blood. In the cross and resurrection of his Son, God has given us everything that we need to live with alongside the terrors of his seeming absence.

-

We will, it seems, to do almost anything to avoid the recognition that something is deeply wrong with all of us

Human beings wish to believe in a pure and good inner self led astray by “cultural forces”; or a conflicted self that is concerned not with righteousness but only with happiness and unhappiness; or a self afflicted by and seeking to throw off the burden of a flawed and inadequate past; or no self at all. We will, it seems, do almost anything, construct almost any story, to avoid the recognition that something is deeply wrong with all of us, that whatever it is causes us to do what is wrong, and that we cannot plausibly blame that wrongdoing wholly on external forces.

-

A history of the hardware store

Why should we care about the survival of these quotidian spaces, with their ten-cent goods, at a time of crisis when many American cities lack affordable housing and clean water? I’d argue that the hardware store is more than a “common ground.” It’s a place of exchange based on values that are evidently in short supply among our political and corporate leaders: competence, intention, utility, care, repair, and maintenance. 8 In an era of black-boxed neural nets and disposable gadgets, hardware stores promote a material consciousness and a mechanical sensibility. They encourage civic forms of accreditation, resistant to metrics and algorithms. At some neighborhood stores, you can stop in for a couple of screws and be waved off from paying at the register.

-

Julian's hazelnut

I saw that [our Lord] is to us everything which is good and comforting for our help. He is our clothing, who wraps and enfolds us for love, embraces us and shelters us, surrounds us for his love, which is so tender that he may never desert us. And so in this sight I saw that he is everything which is good, as I understand.

And in this he showed me something small, no bigger than a hazelnut, lying in the palm of my hand, and I perceived that it was as round as any ball. I looked at it and thought: What can this be? And I was given this general answer: It is everything which is made. I was amazed that it could last, for I thought that it was so little that it could suddenly fall into nothing. And I was answered in my understanding: It lasts and always will, because God loves it; and thus everything has being through the love of God.

In this little thing I saw three properties. The first is that God made it, the second is that he loves it, the third is that God preserves it. But what is that to me? It is that God is the Creator and the lover and the protector. For until I am substantially united to him, I can never have love or rest or true happiness; until, that is, I am so attached to him that there can be no created thing between my God and me. And who will do this deed? Truly, he himself, by his mercy and his grace, for he has made me for this and has blessedly restored me.

-

The Gardener Considers Spring Planting in a February Blizzard

Neat black envelopes, emboldened

By images, offer up their names:

Kale, turnip, radish, pea, and the divine tomato,

Chestnut Chocolate, Pink Brandywine, Atomic Grape.

A litany of desire prayed at the kitchen table. -

Woman is the representative human being before God

Receptivity to God, embodied in the form of woman, is humanity’s ultimate purpose. This is the telos of our existence—saying yes to divine grace and welcoming the inner metamorphosis it brings. Woman, then, is the representative human being before God; she carries the image of this receptivity to which all are beckoned, whether male or female.

Because we are unused to thinking about sex in symbolic terms, it is easy to misunderstand the argument. I am not here suggesting that all women must be mothers in the literal sense, or that women are more spiritual than men, or that men are more proximate to God. These objections forget that we are dealing with symbols—more specifically, a metaphor of the relation, not of God or humanity in isolation. Each sex is telling the same story of divine-human communion through the language of the body, albeit from two distinct angles.

-

Going through the motions with Christian practices

My heritage as a Christian lies in a radically low church group, the acapella churches of Christ, that tends to scorn formal liturgies as empty and meaningless (though we practice weekly communion and stress baptism heavily). Most of us when I was growing up had little experience and less knowledge of such practices, and suspicion of them was thus fairly baseless. However, we did occasionally have members who had left a more formal church, departed Catholics or Lutherans. And in fact these folks tended to speak of the practices of their former churches much as the rest of us did, as stultifying, rigid, “going through the motions.”

-

The strange paradoxes of Christ's life and witness

In his famous description of “thrilling romance of Orthodoxy,” G.K. Chesterton suggests the early church found an “equilibrium of a man behind madly rushing horses.” She “swerved to the left and right,” leaving behind an Arianism that would make Christianity too worldly before repudiating an “orientalism” that would make it too unworldly. “It is easy to be a heretic,” Chesterton goes on, as it is “easy to let the age have its head.” After all, there are an “infinity of angles at which one falls,” but “only one at which one stands.” The whirling adventure of the emergence of orthodoxy required saying ‘no’ to distortions on every side, so that they might preserve an undiluted ‘Yes’ to the strange paradoxes of Christ’s life and witness.

Such a situation is, I think, our own: it is possible to go wrong on matters of sex and marriage in ways besides affirming the licitness of same-sex sexual acts and desires. Indeed, it is possible to allow the spectacular transgressions our society’s broken anthropology has generated to make us inattentive to the same fundamental attitudes and dispositions present within our own midst, subtle and quiet though they might be. I have half wondered whether that is partly the point of the chaos all about us, namely, to fill us all with the self-righteous satisfaction of denouncing obvious wrongs while ignoring the many ways our own communities have imbibed the spirit of our age.

-

A moment of transcendence

“My whole life had been spent waiting for an epiphany, a manifestation of God’s presence, the kind of transcendent, magical experience that lets you see your place in the big picture. And that is what I had with my first compost heap.”

-

We have not shopped in a display of lives

We have not got to where we are by anything so simple as deciding what we wanted to do and then doing it—as if we had shopped in a display of lives and selected one. We have, instead, in the midst of living, and with time passing, been discovering how we want to live, and inventing the ways.

-

Imagining creatures together

I haven’t been conscious before of how invariably when I have sensed or imagined the life of another creature, a tree or bird or animal, I have had to begin by imagining my own absence—as though there was a necessary competition between my life and theirs. I looked upon my ability to imagine myself absent as a virtue. It seems to me now that it was an evasion. I began this morning to feel something truer—the beginning of the knowledge that the other creatures and I are here together.

-

Joy does not break with solidarity

Refusing joy for the sake of suffering does not help those who suffer. The contrary is true. The world needs people who discover the good, who rejoice in it and thereby derive the impetus and courage to do good. Joy, then, does not break with solidarity. When it is the right kind of joy, when it is not egotistic, when it comes from the perception of the good, then it wants to communicate itself, and it gets passed on.

-

There is a kind of love called maintenance

Atlas

-

You are not of a catholic spirit because you are of a muddy understanding

A catholic spirit is not speculative latitudinarianism. It is not an indifference to all opinions: this is the spawn of hell, not the offspring of heaven. This unsettledness of thought, this being “driven to and fro, and tossed about with every wind of doctrine,” is a great curse, not a blessing, an irreconcilable enemy, not a friend, to true catholicism. A man of a truly catholic spirit has not now his religion to seek. He is fixed as the sun in his judgement concerning the main branches of Christian doctrine. It is true, he is always ready to hear and weigh whatsoever can be offered against his principles; but as this does not show any wavering in his own mind, so neither does it occasion any. He does not halt between two opinions, nor vainly endeavour to blend them into one. Observe this, you who know not what spirit ye are of: who call yourselves men of a catholic spirit, only because you are of a muddy understanding; because your mind is all in a mist; because you have no settled, consistent principles, but are for jumbling all opinions together. Be convinced, that you have quite missed your way; you know not where you are. You think you are got into the very spirit of Christ; when, in truth, you are nearer the spirit of Antichrist. Go, first, and learn the first elements of the gospel of Christ, and then shall you learn to be of a truly catholic spirit.

-

Subversive habits of hospitality

While more formal gatherings have their place, to reduce hospitality to “entertaining” is in fact deeply anti-social. By design, it puts up barriers to intimacy, keeping friends (and even family) at arm’s length from one’s real life and real self. It expresses distrust that others could possibly love me as I am, thus smothering true friendship before it can even take root.

Habits of hospitality, on the other hand, are downright subversive in our culture of independence and calculation. They demonstrate that it is not only possible but fruitful and beautiful to share life in a substantive way outside the confines of the nuclear family. And, in so doing, they point to the reality of the common good, not just as a theoretical concept but as a practical one that can animate an authentic Christian community.

-

Scientists may have found an enzyme that eats plastic

Researchers studying a newly-discovered bacterium found that with a few tweaks, the bug can be turned into a mutant enzyme that starts eating plastic in a matter of days, compared to the centuries it takes for plastic to break down in the ocean.

-

Woe unto you if a March thaw fools you

A sweetly warm day in January will commence a soupy thaw and some lifting of saggy winter spirits, but one knows it’s still wintertime. A pleasant day in February will catch a person off guard (and will convince the goose to get to work on her family) but everyone knows that February is changeable, and that a winter storm could still–and probably will–threaten again. But. A string of sun-filled days in March may tease you into believing that winter is done with you for this year. The daffodils and crocus will quickly swallow this, as will the elm and maple trees. The honeybees are great believers in early Spring as well, hungry to begin their work. But woe to the fruit trees with their easily-frozen blossoms if they are gullible enough to believe. And woe to you, beloved, if you are fooled.

-

When mercy looks like justice

If someone were doing something harmful to themselves, would it be merciful or just to stop them? Say, for instance, that you are an engineer, and a neighbor was building a structurally unsound addition to their house, which would likely result in the addition collapsing, potentially injuring someone. And despite your best efforts, they will not listen to your professional counsel. Would it be more merciful or more just to call the city officials, urging them to make an inspection of your neighbor’s handiwork?

On the one hand, it would be just. You would be taking the relevant laws and rules into account, holding them accountable in the process, in such a way as to make them liable to different fines and consequences. They may feel that you overemphasized justice and rule keeping, feeling angry with you for interfering in their private affairs. On the other hand, it would be merciful, for what could be kinder than to do what is necessary to protect the family and possessions of your neighbor from great danger, even in the face of their opposition?

In this case, Plato would say, it would not be merciful to leave them to their own devices, risking their lives and that of their family and guests, and neither would it be just. The only way to truly be merciful is to pursue justice, for only justice will bring about a situation which is good and safe for everyone involved.

-

Breakfast Song

Come let us to the fields away,

For who would eat must toil,

And there’s no finer work for man,

Than tilling of the soil. -

Lies aren't homeopathic

The film’s promotion of self-esteem is relentless and typically American, in that it takes the idea of believing in yourself to the point of unconscious cruelty and then past it. The script endlessly belabors the point that Meg is the most important thing in the universe. I know that this is intended as counterprogramming for a world that tells black girls they’re worthless, but lies aren’t homeopathic–you can’t grow someone’s self-esteem to the right degree by encouraging her to be a solipsist. All that’ll do is give her another set of reasons to hate herself, since the human being never seems more ridiculous to itself than when it mistakes itself for God. (Why do you think so many white men are weirdos?)

-

Three Poems at Easter

A Happy Easter to my friends on the Western liturgical calendar: Christ is risen! Here are three poems I love for the day.

-

My father's garden

On the outskirts, in a waste of clay and rock

unearthed when the Interstate went through,

he made his garden—leveled and cleared

the gutted soil. Then in early spring

he brought sacks of sphagnum and guano,

water in gallon jugs, since the spring rains

were never enough, and small bags of seed

with odd names: Early Girl and Black Magic;

Big Max, Straight Eight and Kentucky Wonder.

Testing, holding fast to that which was good.

-

Digital monasticism

We can usefully frame the choice to delete Facebook or abstain from social media or any other act of tech refusal by (admittedly loose) analogy to the monastic life. It is not for everyone. The choice can be costly. It will require self-denial and discipline. Not everyone is in a position to make such a choice even if they desired it. And maybe, under present circumstances, it would not even be altogether desirable for most people to make that choice. But it is good for all of us that some people do make that choice.

-

The crux of the matter

A: “The crux of the matter is, how can we make archaeology cool again?”

B: “We can’t!”

-

Luther: I am not worthy to rock this little babe or wash its diapers

What then does Christian faith say to this? It opens its eyes, looks upon all these insignificant, distasteful, and despised duties in the Spirit, and is aware that they are all adorned with divine approval as with the costliest gold and jewels. It says, “O God, because I am certain that you have created me as a man and have from my body begotten this child, I also know for certain that it meets with your perfect pleasure. I confess to you that I am not worthy to rock this little babe or wash its diapers. Or to be entrusted with the care of the child and its mother. How is it that I, without any merit, have come to this distinction of being certain that I am serving your creature and your most precious will? O how gladly will I do so, though the duties should be even more insignificant and despised. Neither frost nor heat, neither drudgery nor labor, will distress or dissuade me, for I am certain that it is thus pleasing in your sight.”

God, with all his angels and creatures, is smiling, not because that father is washing diapers, but because he is doing so in Christian faith.

-

Psychological gravity keeps us on social media

It is psychological gravity, not technical inertia, however, that is the greater force against the open web. Human beings are social animals and centralized social media like Twitter and Facebook provide a powerful sense of ambient humanity—the feeling that “others are here”—that is often missing when one writes on one’s own site. Facebook has a whole team of Ph.D.s in social psychology finding ways to increase that feeling of ambient humanity and thus increase your usage of their service.

When I left Facebook eight years ago, it showed me five photos of my friends, some with their newborn babies, and asked if I was really sure. It is unclear to me if the re-decentralizers are willing to be, or even should be, as ruthless as this. It’s easier to work on interoperable technology than social psychology, and yet it is on the latter battlefield that the war for the open web will likely be won or lost.

-

In this place that is waste, there shall again be habitations

“Thus says the LORD of hosts: In this place that is waste, without man or beast, and in all of its cities, there shall again be habitations of shepherds resting their flocks.”

-

The uncommon worth of wire

When I took over the farm following my grandfather’s death, I initially despaired at all the loose bits and pieces that littered the place. Wire was my special enemy, for the barns were everywhere cluttered with it – wire salvaged from telephones, from appliances, from who-could-tell-where. I accumulated buckets of wire with a plan to dispose of them. Mercifully, I never got round to it, for I quickly learned the uncommon worth of wire. For example, it presently holds the muffler to my truck, secures the busted PTO cover on my bushhog, and seams caging around fruit-tree saplings, the better to protect them from the depredations of deer. My only concern about wire now is that I might need more.

The stock images sometimes used to depict the pitiable conditions or pathologies of the rural poor – images of homeplaces surrounded by wreckage and ‘trash’ – tell a bigger story if you know how to read them. The broken-down car in the yard contains parts that still have use in them if need arises. That rusty freezer on the porch probably contains the dog’s food, since nothing beats an old freezer for storing feed where unsanctioned animals can’t get at it. Put plainly, if there is wire everywhere, there’s probably a reason. And if you can’t see the reason, there’s probably a reason for that too.

-

A Christianity not concerned with one-upping the world

This, of course, is very similar to the conversion accounts of two other writers I admire—Sheldon Vanauken and C. S. Lewis. For both of these men, the surprising brilliance of Christian writers helped them come to faith and then adjust to being, unexpectedly and somewhat reluctantly, Christian themselves. But even more important was the fact that the Christianity that both of these men encountered (at Oxford, in both cases) was not scared of the world nor was it concerned with somehow one-upping the world. It was, rather, deeply at home in it, fascinated by it, and convinced that the truth of Christianity did not negate the truths they came to prior to conversion, but somehow enriched them.

-

McMansion Hell as public scholarship

We’ve built up all kinds of personal databases of buildings. Some of them are pretty general: split level houses, gas stations, water towers, etc. Some are more specific: fast food chains (new), fast food chains that haven’t been remodeled yet, “new” apartment buildings, dilapidated hotels by the sides of highways, office parks, churches that used to be something else, etc. (I personally have a category called hospitals built in the early 00s that were doing Postmodern Prairie chic.)

. . .

Like I said earlier, a lot of the time we don’t have a common language to describe these buildings. Some people come up with pejorative names to describe built phenomenon (the McMansion is the prime example of this). Others try to define buildings by decade (e.g. 70s malls vs 80s malls).

However, this lack of common language hasn’t stopped hundreds of makeshift historians from relentlessly categorizing buildings, styles, aesthetics, and anything else that can be filmed, photographed, or written about online. And frankly, this work is fascinating, it is important, it is exciting, and it needs to be done.

-

Poultry farmers below the poverty line

Roughly 97 percent of poultry farmers in the United States are “contract farmers.” This means each farm has an exclusive contract with a gigantic corporation like Tyson, Pilgrim’s Pride, or Perdue. The corporation gives the farmer the chicks, which the farmer raises to slaughtering age, then ships them back off to the corporation for processing. The corporation has an insane level of control over the farmer: they can decide how many and what quality of chicks to give, they can demand at a moment’s notice that the farmer make significant and expensive changes to the farm, and the farmer is legally not allowed to sue for unfair practices. In one lawsuit, the word “cartel” was used to describe chicken producers. It is, without exaggeration, indentured servitude. It also does not really work; roughly 71 percent of contract farmers are at or below the federal poverty line, according to a Pew survey.